ES

Executive Summary

This special report assesses new knowledge since the IPCC 5th Assessment Report (AR5) and the Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5°C (SR15) on how the ocean and cryosphere have and are expected to change with ongoing global warming, the risks and opportunities these changes bring to ecosystems and people, and mitigation, adaptation and governance options for reducing future risks. Chapter 1 provides context on the importance of the ocean and cryosphere, and the framework for the assessments in subsequent chapters of the report.

All people on Earth depend directly or indirectly on the ocean and cryosphere. The fundamental roles of the ocean and cryosphere in the Earth system include the uptake and redistribution of anthropogenic carbon dioxide and heat by the ocean, as well as their crucial involvement of in the hydrological cycle. The cryosphere also amplifies climate changes through snow, ice and permafrost feedbacks. Services provided to people by the ocean and/or cryosphere include food and freshwater, renewable energy, health and wellbeing, cultural values, trade and transport. {1.1, 1.2, 1.5}

Sustainable development is at risk from emerging and intensifying ocean and cryosphere changes. Ocean and cryosphere changes interact with each of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Progress on climate action (SDG 13) would reduce risks to aspects of sustainable development that are fundamentally linked to the ocean and cryosphere and the services they provide (high confidence1). Progress on achieving the SDGs can contribute to reducing the exposure or vulnerabilities of people and communities to the risks of ocean and cryosphere change (medium confidence). {1.1}

Communities living in close connection with polar, mountain, and coastal environments are particularly exposed to the current and future hazards of ocean and cryosphere change. Coasts are home to approximately 28% of the global population, including around 11% living on land less than 10 m above sea level. Almost 10% of the global population lives in the Arctic or high mountain regions. People in these regions face the greatest exposure to ocean and cryosphere change, and poor and marginalised people here are particularly vulnerable to climate-related hazards and risks (very high confidence). The adaptive capacity of people, communities and nations is shaped by social, political, cultural, economic, technological, institutional, geographical and demographic factors. {1.1, 1.5, 1.6, Cross-Chapter Box 2 in Chapter 1}

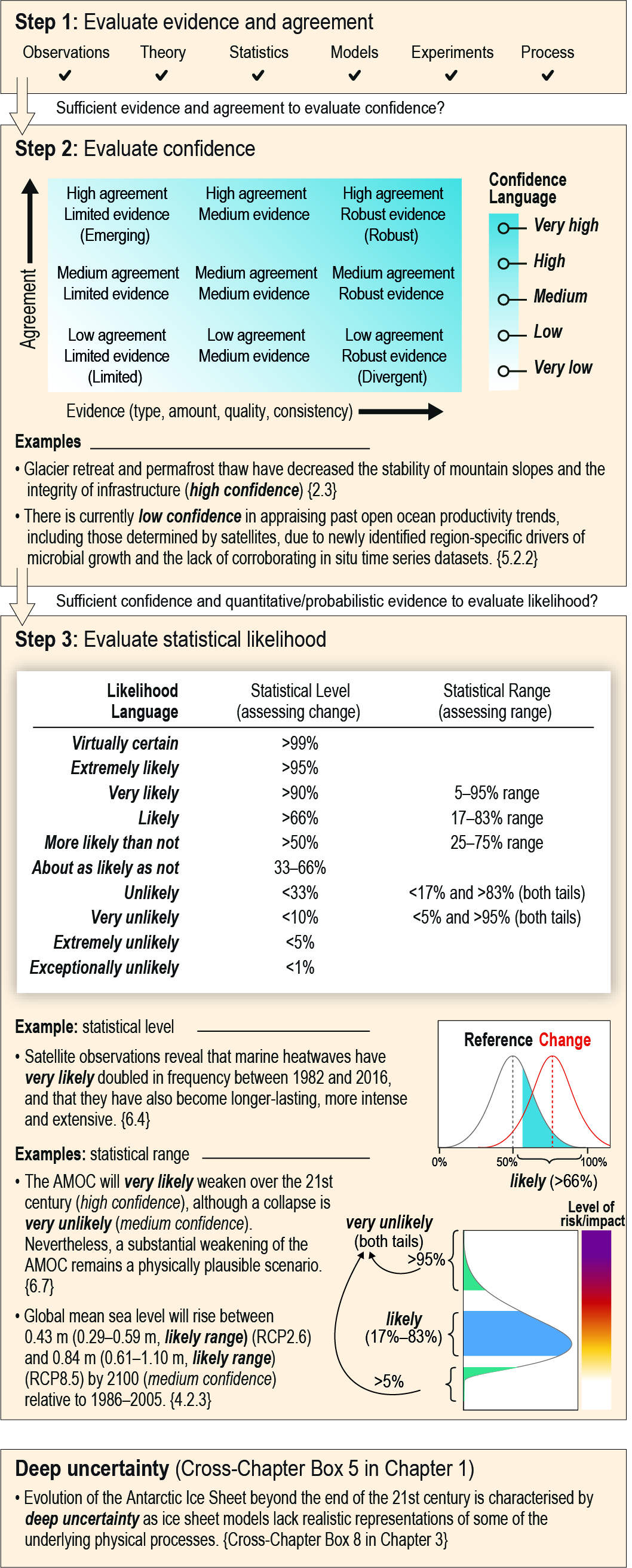

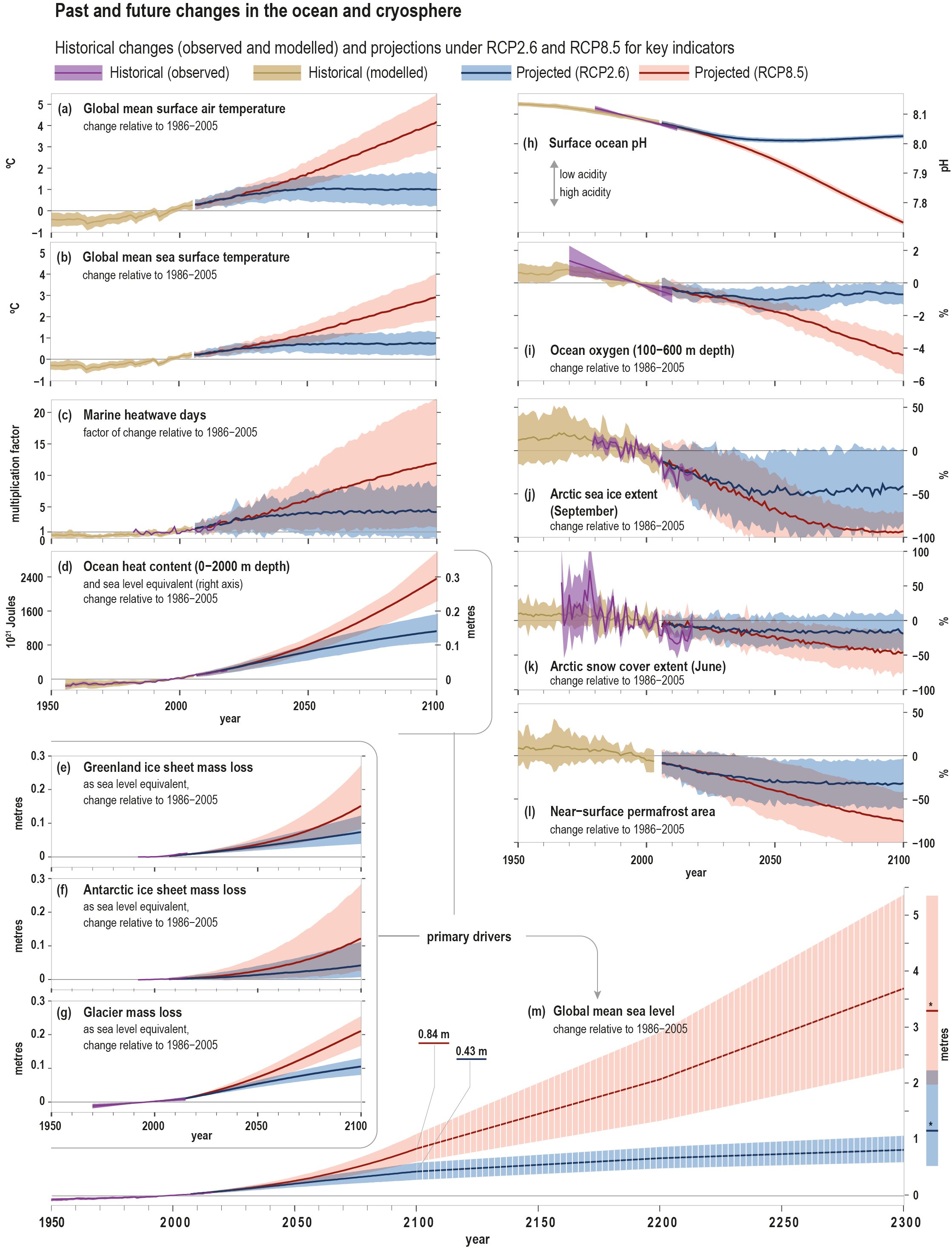

Ocean and cryosphere changes are pervasive and observed from high mountains, to the polar regions, to coasts, and into the deep ocean. AR5 assessed that the ocean is warming (0 to 700 m: virtually certain2; 700 to 2,000 m: likely), sea level is rising (high confidence), and ocean acidity is increasing (high confidence). Most glaciers are shrinking (high confidence), the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets are losing mass (high confidence), sea ice extent in the Arctic is decreasing (very high confidence), Northern Hemisphere snow cover is decreasing (very high confidence), and permafrost temperatures are increasing (high confidence). Improvements since AR5 in observation systems, techniques, reconstructions and model developments, have advanced scientific characterisation and understanding of ocean and cryosphere change, including in previously identified areas of concern such as ice sheets and Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC). {1.1, 1.4, 1.8.1}

Evidence and understanding of the human causes of climate warming, and of associated ocean and cryosphere changes, has increased over the past 30 years of IPCC assessments (very high confidence). Human activities are estimated to have caused approximately 1.0°C of global warming above pre-industrial levels (SR15). Areas of concern in earlier IPCC reports, such as the expected acceleration of sea level rise, are now observed (high confidence). Evidence for expected slow-down of AMOC is emerging in sustained observations and from long-term palaeoclimate reconstructions (medium confidence), and may be related with anthropogenic forcing according to model simulations, although this remains to be properly attributed. Significant sea level rise contributions from Antarctic ice sheet mass loss (very high confidence), which earlier reports did not expect to manifest this century, are already being observed. {1.1, 1.4}

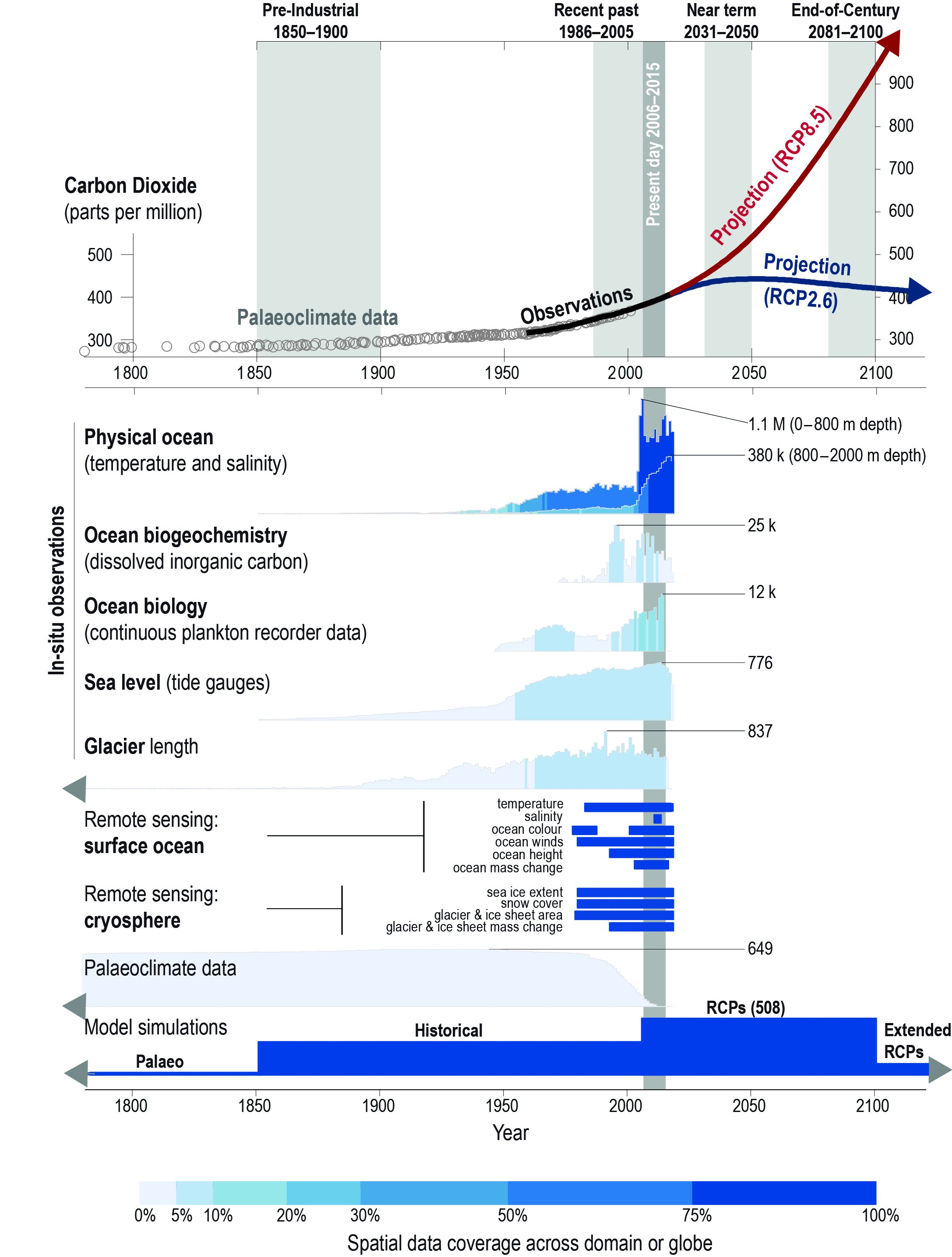

Ocean and cryosphere changes and risks by the end-of-century (2081-2100) will be larger under high greenhouse gas emission scenarios, compared with low emission scenarios (very high confidence). Projections and assessments of future climate, ocean and cryosphere changes in the Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate (SROCC) are commonly based on coordinated climate model experiments from the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 5 (CMIP5) forced with Representative Concentration Pathways (RCPs) of future radiative forcing. Current emissions continue to grow at a rate consistent with a high emission future without effective climate change mitigation policies (referred to as RCP8.5). The SROCC assessment contrasts this high greenhouse gas emission future with a low greenhouse gas emission, high mitigation future (referred to as RCP2.6) that gives a two in three chance of limiting warming by the end of the century to less than 2°C above pre-industrial. {Cross-Chapter Box 1 in Chapter 1}

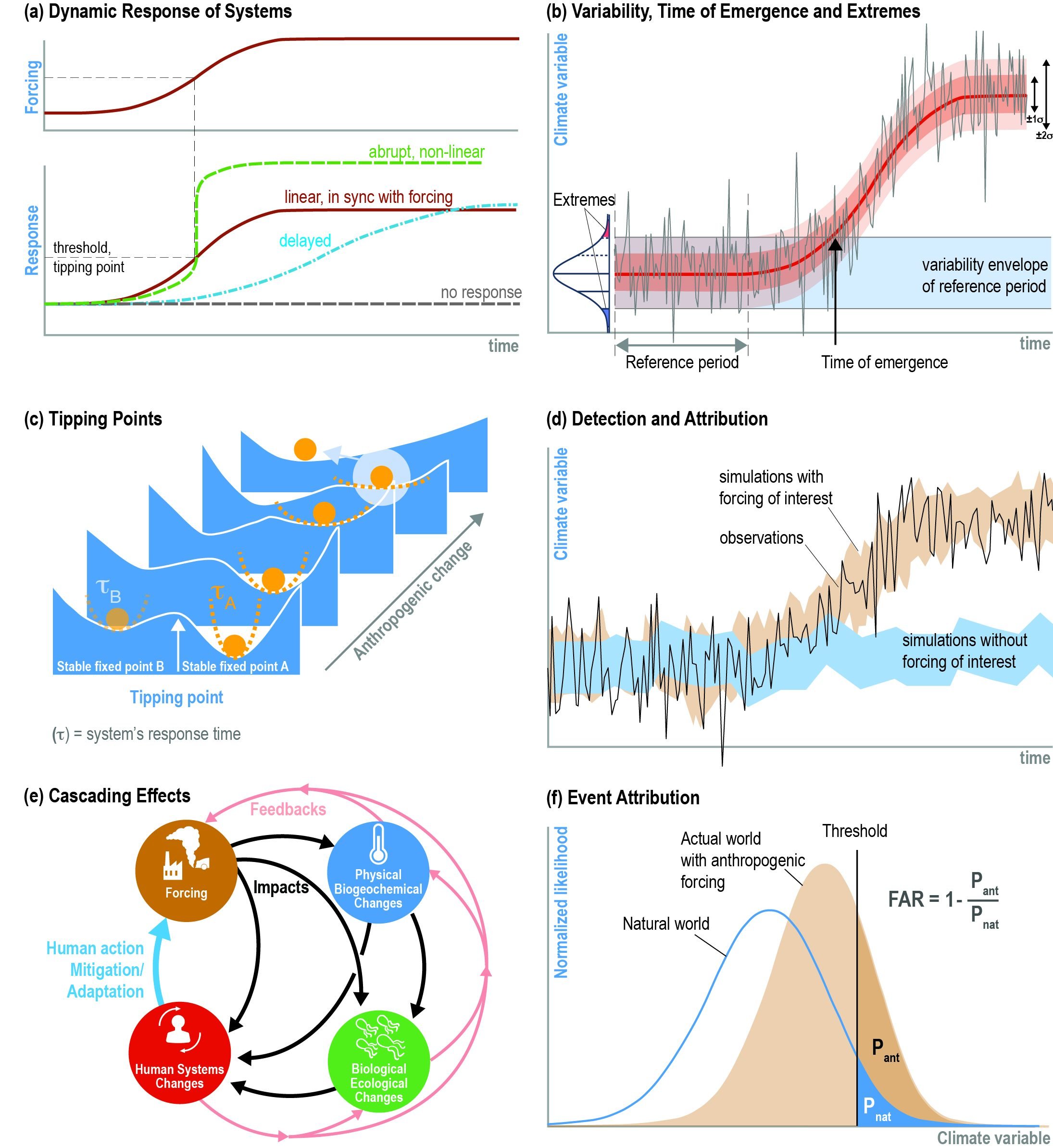

Characteristics of ocean and cryosphere change include thresholds of abrupt change, long-term changes that cannot be avoided, and irreversibility (high confidence). Ocean warming, acidification and deoxygenation, ice sheet and glacier mass loss, and permafrost degradation are expected to be irreversible on time scales relevant to human societies and ecosystems. Long response times of decades to millennia mean that the ocean and cryosphere are committed to long-term change even after atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations and radiative forcing stabilise (high confidence). Ice-melt or the thawing of permafrost involve thresholds (state changes) that allow for abrupt, nonlinear responses to ongoing climate warming (high confidence). These characteristics of ocean and cryosphere change pose risks and challenges to adaptation {1.1, Box 1.1, 1.3}.

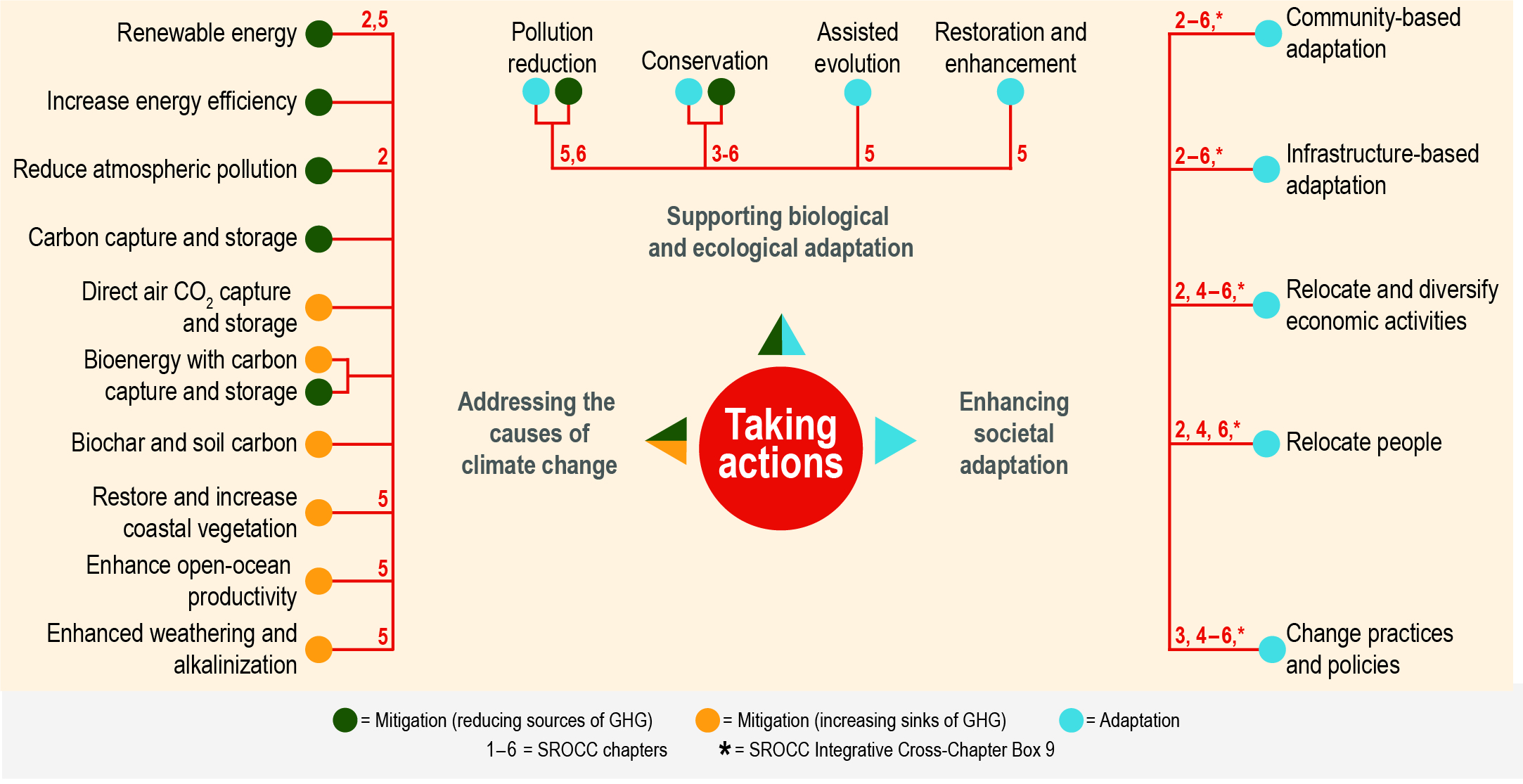

Societies will be exposed, and challenged to adapt, to changes in the ocean and cryosphere even if current and future efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions keep global warming well below 2°C (very high confidence). Ocean and cryosphere-related mitigation and adaptation measures include options that address the causes of climate change, support biological and ecological adaptation, or enhance societal adaptation. Most ocean-based local mitigation and adaptation measures have limited effectiveness to mitigate climate change and reduce its consequences at the global scale, but are useful to implement because they address local risks, often have co-benefits such as biodiversity conservation, and have few adverse side effects. Effective mitigation at a global scale will reduce the need and cost of adaptation, and reduce the risks of surpassing limits to adaptation. Ocean-based carbon dioxide removal at the global scale has potentially large negative ecosystem consequences. {1.6.1, 1.6.2, Cross-Chapter Box 2 in Chapter 1}

The scale and cross-boundary dimensions of changes in the ocean and cryosphere challenge the ability of communities, cultures and nations to respond effectively within existing governance frameworks (high confidence). Profound economic and institutional transformations are needed if climate-resilient development is to be achieved (high confidence). Changes in the ocean and cryosphere, the ecosystem services that they provide, the drivers of those changes, and the risks to marine, coastal, polar and mountain ecosystems, occur on spatial and temporal scales that may not align within existing governance structures and practices (medium confidence). This report highlights the requirements for transformative governance, international and transboundary cooperation, and greater empowerment of local communities in the governance of the ocean, coasts, and cryosphere in a changing climate. {1.5, 1.7, Cross-Chapter Box 2 in Chapter 1, Cross-Chapter Box 3 in Chapter 1}

Robust assessments of ocean and cryosphere change, and the development of context-specific governance and response options, depend on utilising and strengthening all available knowledge systems (high confidence). Scientific knowledge from observations, models and syntheses provides global to local scale understandings of climate change (very high confidence). Indigenous knowledge (IK) and local knowledge (LK) provide context-specific and socio-culturally relevant understandings for effective responses and policies (medium confidence). Education and climate literacy enable climate action and adaptation (high confidence). {1.8, Cross-Chapter Box 4 in Chapter 1}

Long-term sustained observations and continued modelling are critical for detecting, understanding and predicting ocean and cryosphere change, providing the knowledge to inform risk assessments and adaptation planning (high confidence). Knowledge gaps exist in scientific knowledge for important regions, parameters and processes of ocean and cryosphere change, including for physically plausible, high impact changes like high end sea level rise scenarios that would be costly if realised without effective adaptation planning and even then may exceed limits to to adaptation. Means such as expert judgement, scenario building, and invoking multiple lines of evidence enable comprehensive risk assessments even in cases of uncertain future ocean and cryosphere changes. {1.8.1, 1.9.2, Cross-Chapter Box 5 in Chapter 1}